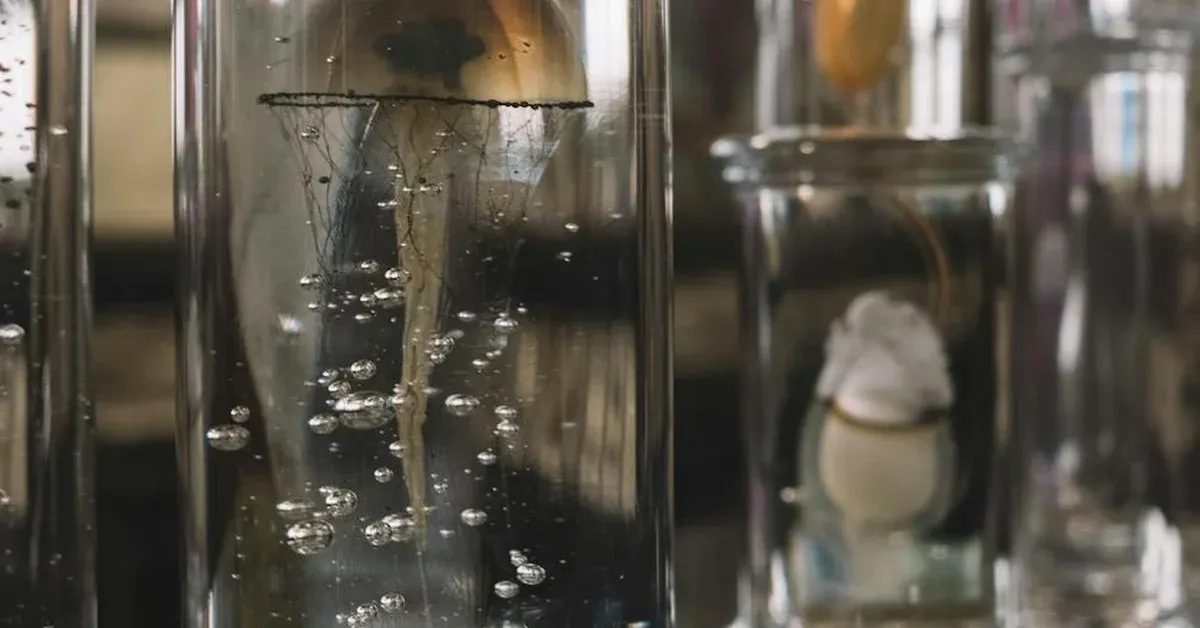

Forget what you thought you knew about sleep. Your brain might be entirely optional for a good night’s rest. Scientists discovered something remarkable: the upside-down jellyfish, Cassiopea, goes to sleep. Yes, a creature without a centralized brain, one that’s been around for over 600 million years, needs its rest just like you do. I guess this isn’t just a quirky biological fact. It’s a fundamental shift in our understanding of what sleep is and why every living thing seems to need it, challenging deeply held ideas about consciousness and rest.

How scientists caught jellyfish napping

Before you dismiss this as simple observation, know that researchers didn’t just guess the jellyfish were chilling out. They tested rigorously for the three established hallmarks of sleep. First, the jellyfish became noticeably less active at night, reducing their bell pulsing frequency. This decrease in activity during a predictable period mirrors how most animals settle down.

Second, when disturbed during their downtime with gentle water pulses, they were significantly slower to react. This groggy delay in reaction is a key indicator of true sleep. Most compellingly, if scientists kept the jellyfish awake during their usual rest cycle, they exhibited a classic rebound effect. The jellyfish would then sleep longer and more deeply to compensate for the lost rest, showing sleep deprivation and the biological need for recovery. This consistent behavior, observed in animals ranging from fruit flies to humans, suggests a deeply conserved biological drive for sleep, even without a complex brain dictating the process.

Why do we sleep and guess what bodies repair

This discovery challenges long-held assumptions about sleep. For decades, the prevailing idea was that sleep was linked to higher brain function, serving complex processes like memory consolidation or clearing neural waste products. But jellyfish, with their diffuse nerve net and complete lack of a central processing unit, operate on fundamentally different biological architecture. Their slumber implies that sleep’s evolutionary origins predate the emergence of complex brains entirely, placing its roots much further back in the tree of life.

Researchers suggest that sleep might be a more ancient, fundamental cellular process rather than a purely neurological one. It’s a mechanism so crucial for basic biological function that evolution embedded it into even the simplest multicellular organisms. Just as we’ve learned about the deep evolutionary roots of conditions like ADHD, whose genes trace back 45,000 years to Neanderthals, the drive to sleep might be an even more primal biological command. You can read more about the initial discovery in this PubMed Central study.

Sleep helps bodies repair cellular damage

If jellyfish aren’t consolidating memories or dreaming, what are they doing during their rest state? Emerging research points to vital cellular maintenance. One leading hypothesis is that sleep is essential for neuronal DNA repair. While organisms are awake, their cells are active, metabolizing resources and generating byproducts that can damage delicate DNA. Sleep provides a crucial window where the energy demands of active functioning are reduced, allowing cellular repair mechanisms to work efficiently.

This repair process isn’t just for our brains. It’s a universal requirement for all active cells. Sleep serves as a protective state, allowing the body’s cells to mend themselves from daily wear and tear. Observations that jellyfish and sea anemones extend their sleep when neuronal DNA is experimentally damaged solidify the idea that downtime is directly linked to cellular recovery. This suggests that the cause of a lack of immediate responsiveness during sleep is precisely to facilitate these critical cellular operations, processes that cannot happen as efficiently when the organism is fully active. More details on these findings can be found via HHMI News.

The idea that sleep causes a lack of consciousness to facilitate deeper cellular work fundamentally redefines its purpose. It moves beyond a purely brain-centric view to a body-wide imperative, a period for every cell to catch up on maintenance. This perspective could inform everything from understanding chronic fatigue to developing new therapeutic approaches for neurodegenerative diseases, where cellular repair is often compromised, or even for optimizing recovery in humans who need to repair awake capabilities after intense physical or mental exertion.

What jellyfish teach us about rest

The humble jellyfish, pulsing gently at the bottom of the ocean, is forcing us to rethink biological understanding. Their sleepy habits suggest that the core function of rest isn’t necessarily about sophisticated thought or learning, but something far more basic: cellular upkeep and DNA repair. This implies that sleep is an evolutionarily conserved behavior, a fundamental requirement for multicellular life that emerged long before specialized organs or centralized brains. The discovery highlights a profound truth: the need for recovery is a defining characteristic of life itself.

This ancient drive for rest, present in creatures with the simplest nervous systems, highlights how deeply rooted certain biological strategies are. It’s not just our complex human brains that benefit from powering down. It’s practically every cell in every organism, from the simplest to the most complex. From the surprising strategies of other creatures, like how spiders build giant fake selves to trick predators, to the inherent strengths of diverse human neurotypes, such as supercurious ADHD brains that process information differently, the natural world constantly reveals unexpected depth. The jellyfish, in its silent slumber, reminds us that some of life’s most profound mysteries are hidden in plain sight. I guess we’re only beginning to understand what it truly means to be alive and, crucially, to be asleep.